By Mia Ryder (pen name)

bookboxchicago33@gmail.com

“Henrietta!” screeched Aunt Lil. The minute Henny walked into the kitchen, Aunt Lil demanded, “Where did Henrietta go? I need my reading glasses.”

“It’s me, Henrietta,” Henny replied gently as she took the reading glasses from around her aunt’s neck and placed them on her nose. Aunt Lil unfolded the pages of the Chicago Tribune and soon became absorbed in a story.

Aunt Lil was once a vibrant and beloved columnist for this newspaper. To see her now, it was as if someone had shaken the gems out of her jewelry box. Dementia was a thief.

“Joseph is always hiding my glasses,” Lil muttered, irritated with her long-dead husband whom she still interacted with daily. At least she didn’t have to miss him, Henny thought.

The Marvell family, which was composed of Henny, her mother Nancy, great-aunt Lil, and their dog Brontë, lived in a bungalow on the Northwest side of Chicago in a neighborhood called Portage Park. Henny and her mom took turns caring for Aunt Lil when Henny was in high school or her mom was working the night shift at the hospital. Thanks to the hybrid learning model necessitated by the pandemic, Henny was on call for Aunt Lil more often now.

Henny showed Aunt Lil the book she had just found in the book box down the street. “It’s called Chantilly, and, look here, Aunt Lil, it’s signed by the author, Francis Thrash. She’s from Chicago.”

“From Chicago? Of course she is; her house is in Portage Park.”

Henny pulled out a chair and sat dumbfounded. How weird that Aunt Lil could extract that tidbit from her brain even when she didn’t recognize her family half the time. She shook her head and then began thumbing through her new book. Reading was her ultimate escape—mystery novels, mostly—especially since she didn’t get out much these days. She was so engrossed by her book that she almost didn’t notice the extra coffee cup on the table. Aunt Lil had her knotty fingers wrapped around one mug while a second one sat across the table.

“Aunt Lil, whose coffee cup is this?”

“The man’s.”

“What man?”

“The MAN who comes to chat with me.”

When her aunt spoke to her dead husband or a myriad of other imagined visitors, she and her mom would nod politely and sneak a smile to each other. They were getting fairly used to it. But this coffee cup …

“Aunt Lil, you know you’re not supposed to let anyone in the house when I walk Brontë.”

“Hey smart mouth, I’m the grownup and you’re the kid, remember? Anyway I didn’t let him in, he had the key your dad gave him.”

Henny tilted her head to stare at her aunt like a quizzical puppy. Henny’s father was an Alderman in their ward who died seven years ago of a heart attack, which absolutely did not explain why there was a second coffee cup on the kitchen table. Henny’s alarm grew, and she started to get that tunnel-visioned head rush that would happen whenever her anxiety set in. She took a deep breath and realized that she wasn’t going to get a meaningful answer from Aunt Lil. She humored her anyway.

“Your gentleman caller have a name?” Henny probed.

“Daniel Radcliff,” Aunt Lil replied.

“Harry Potter came to see you?”

“See for yourself. He’s coming back for a second cup.”

Henny almost fell out of her chair when she heard the toilet flush down the hall. The sound of footsteps neared, followed by a voice behind her, “Hey Henny, long time no chit chat. What up, girrrl.”

Alderman Jordanski, once her dad’s political rival and now a schmoozy family friend, sauntered in. Henny didn’t like the way his eyes drifted down to her chest or the way he flirted with her mom. But he did bring them produce and flowers from the Farmer’s Market all the time, so he must not be a complete slimeball, Henny thought. He just had the hots for her mom; gross. She really hated the way he tried to sound hip when he talked to her.

“Greetings, Mr. Jordanski. Your lingo is antiquated, but yeah, hi.”

“Oh Henny, you’re such an old soul.”

Translation: You’re a weirdo, Henny thought with a smile to herself. She was okay with that. She’d rather hang out with her dog and bury herself in a good book than congregate outside the Q-Mart with her boring classmates. And she completely shunned social media. TikTok was for clocks.

“Hey, who’s reading that piece of trash?” Jordanski had noticed Chantilly resting on the table. “I didn’t know that nut job finished her book,” he snorted.

Henny grabbed the book off the table before he could get near it. His eyes flashed menace, then squinted as he forced a smile.

“Don’t believe everything you read, Henny-kins.”

“I found it in the book box this morning. It’s called Chantilly by Francis Thrash, like the lace. An intricate weave.” The metaphor will be lost on him, she thought.

“Right —Francis Thrash the whacko. Those book box free lending libraries went into the neighborhoods after I took over as Alderman,” said Jordanski, forever campaigning. Henny pantomimed puking behind his back, which Jordanski caught in a reflection on the toaster.

“After my dad proposed them in his last term,” Henny clarified.

“Anyway, nice chatting with you Lil,” Jordanski said, ignoring Henny’s remark.

“Alohomora!” Aunt Lil replied by casting a spell from Harry Potter.

“Yeah, aloha to you, too,” said Jordanski the Clueless.

#

It was on her walk with Brontë that Henny had spied Chantilly in the book box that morning. The book box free lending library sat between two blanket-sized front yards. It was just a wooden box on a post with a peaked roof, glass door and books crammed inside, occasionally packaged food. There was a faded cardboard “Welcome Spring” decoration stapled to the side even though it was autumn. The book box was a quaint thing that reminded Henny of the good intentions of human beings. Henny checked it whenever she passed. The last several times she had looked, there had only been the same old contents—a cocktail recipe book circa 1970, Frommer’s Guide to Spain 1999, a water-damaged Charlotte’s Web, a few well-worn women’s magazines, a self-help guide for letting go of guilt, paperback romance novels, a few packets of ramen noodles, and a can of oysters that looked older than the cocktail recipe book. Chantilly was unlike the other books; the spine wasn’t cracked and the pages weren’t stained or dog-eared. Henny ran her finger over the author’s name on the cover; Francis Thrash. The new book smell gave Henny the shivers. She snagged it and vowed to add another book and a can of soup on her next visit. That would maintain the balance of the book box—take and give, ebb and flow—and add to Henny’s good karma.

#

After Jordanski left their house that morning, Henny set out to devour Chantilly, but it was more like the book devoured her. She was captivated by the tale of a multi-generational Chicago family and its dark web of secrets. The family was tangled up in local politics, much like her own family. That thought took her back to Jordanski. What was he doing in her house today, anyway? Why the heck did he have keys? And why did Henny feel a strong urge to change the locks?

When Henny heard her mother come home, she realized that she had been reading for most of the day. She took a break to share some mac and cheese with her mom.

“Did you know Mr. Jordanski has keys to our house, Mom?”

“Sure, he was going to help me get that air conditioner out of the window upstairs. He’ll come by when he can. Busy man.”

“He was here today.”

“Huh. Okay.”

“I’m not a fan.”

“Noted.”

Clearly her mom wasn’t concerned. Henny hurried to put the dishes away and get back to her book, but first, she’d pull out one of Aunt Lil’s old journals to see if one of them contained information about Francis Thrash. She and her mom saved Aunt Lil’s planners and journals for the day when they’d need to invite people to Aunt Lil’s memorial. It was practical and morbid at the same time. You never saw Aunt Lil without a journal clutched under her arm back in her heyday as a reporter. Many of her sources were listed here in her own coded system to conceal their identities. Henny thumbed through the pages looking for the name Francis Thrash. She admired her Aunt Lil and liked to think that she had inherited her once keen eye for investigation.

Sadly, there wasn’t a “Thrash” under the T’s. But Henny knew her Aunt Lil didn’t always color within the lines, even when she had her wits about her. Henny stared at her aunt’s curly-cue handwriting in the margins, trying to decipher the code she used to hide her sources. Some of the listings were accompanied by a word or phrase and a series of numbers. She combed through every page. Eventually, her eyes felt like two bags of sand so she called it quits. Tomorrow was an in-school day, so she’d have to survive a barrage of awkward social encounters and mind-numbing lectures before she could get back to her quest to find her new favorite author.

The minute Henny woke up in the morning, she remembered something she saw in one of Aunt Lil’s journals. It had taken some overnight marinating in her brain, but there it was. She remembered seeing the word “wallop” and numbers scrawled in the margin. Bingo! Henny thought, exuberated. Her Aunt Lil used to love crossword puzzles. What’s a six-letter word for “wallop?” Thrash, as in “Francis Thrash,” just like a crossword clue and solution. That had to be Aunt Lil’s code. While she got dressed, Henny’s head swam with crossword puzzle squares and other clues, like Toilet Offspring for Johnson, or Hitched Year for Mariano. Once she figured out “wallop,” she saw answers everywhere. With a breakfast bar in hand, Henny snatched the old journal off the shelf again and flipped through until she found the right page. The seven-digit number had to be a phone number. Should she call it? That would be weird. What would she say if someone picked up? “I found the book you stashed in the book box and now I’m obsessed with you”?

Henny thought about what Aunt Lil would do back in her investigative reporter days. For Henny’s eighth birthday, Aunt Lil had gifted her niece a full set of Nancy Drew books and had gone on about the brilliance of this fictional sleuth. So, Henny would do this Nancy Drew style and follow the clues, but allow herself just one assist from technology. A modern Nancy Drew would, right? Using Google felt like cheating. But Henny remembered her dad doing reverse phone number searches back in the day when cranks would leave threatening messages. He even let her type in the numbers.

Henny opened her laptop and tried searching for the numbers from Aunt Lil’s journal. She added different prefixes—773, 630, 312—and tried the numbers forward and backward. Backward was the trick. Something called “U.S. People Search” popped up in big, flashy letters scrolling “SUCCESS” across the screen. Her search let loose a waterfall of random information and solicitations for paid criminal background checks. They teased Henny with just the name, age, and address. There at the top of the list was Francis Thrash, age 63. Last known address was blocks away! Henny’s heart fluttered. There was no question Henny would find a way to meet her. But how to approach her? Maybe she’d just do some Nancy Drew-style observation first while she built up the nerve.

“Henny, let’s go!” her mother called her to leave for school. As a senior now, Henny had mastered the drill—blend in, get the work done, and get out. That was the only way she could avoid the panic attacks that plagued her. Hiding behind the required face mask helped, too.

Author Francis Thrash was all Henny could think about at school. Henny was relieved when she finally made it home to resume her quest. Brontë greeted her by spinning in circles, signaling she wanted to go for a walk. Perfect,Henny thought. We’ll make sure to pass by Francis’s home. For the book box, Henny grabbed a can of tomato soup and an old copy of A Wrinkle in Time by Madeleine L’Engle, one of her favorites.

On the walk, Brontë did her usual sniffing around, as if it was her job to inspect and mentally catalog every form of plant life on the block. She would lock onto each scent until it was thoroughly sniffed to her satisfaction. It took an eternity to walk even a few blocks. They eventually arrived at the book box to deposit their offerings and inspect its contents. A funny thing about the book box was that Henny never saw anyone in the act of taking or adding items; she just observed the change of inventory after the fact.

Once they made their way to the author’s house, Henny realized she had passed this house hundreds of times. It was an unremarkable brick bungalow, just like most of the houses on the block, but somehow plainer; no fall wreath to adorn the door, no chalk art to brighten the sidewalk, no cat peeping out the window. A few wet newspapers were stuck under the overgrown bushes, and the old-fashioned roll-up window shades were drawn tightly. The bungalow’s facade had a lifeless expression, like someone in a coma. This house didn’t seem suited to her vibrant author crush, but maybe she was one of those literary artists who focused on her craft and not on her home. Brontë was locked onto a good sniff, so Henny took the opportunity to stand and stare from afar. She imagined Francis inside, tapping away at her computer, or maybe even a typewriter, absorbed in her next novel.

One of the three window shades fluttered. Henny looked away quickly so as not to get caught staring. She felt a dull throbbing in her head and heard a whisper of the words “book box” pulsing in her mind. The shade fluttered harder. Brontë looked up and froze. The throbbing in Henny’s head worsened and Henny feared this was the onset of a panic attack. She tried to steal a glance from the corner of her eye to see if anyone was nearby and might notice that something was amiss. As if the windows caught her gaze, all three shades fluttered and banged more insistently. Brontë whined and pulled hard on her leash. Henny had to sprint to keep up as Brontë pulled her back home. Henny sat with her faithful pup, petting her until the dog stopped panting and she herself felt calm enough to breathe. What the blazes just happened at that house? It felt as if the house knew she was spying and was somehow trying to get her attention.

Despite this weird experience, Henny felt compelled to return to the strange house later that night, alone. Her curiosity won over her fear. She filled the time until then by doing Algebra homework, making spaghetti for her mom and aunt, and watching Wheel of Fortune while they ate. Henny filled her thoughts with the word games her aunt used to love and the secret code she had used to conceal her sources. She studied her Aunt Lil’s face as Vanna revealed the vowels to see if there was any spark of remembrance; she saw none.

It was near midnight when Henny was sure her mom and Aunt Lil were sound asleep before slipping out of bed. Once outside, she pulled the hood of her sweatshirt over her head. The neighborhood was dead silent. She saw the beady eyes of a possum catch the streetlight as it peered from a neighbor’s bushes, watching her, afraid of her … or maybe forher? In just a few moments, she was staring once again at the shut-eyed house of Francis Thrash. It was hard to say for how long she stood there staring at the house but not seeing a darn thing. She felt a little crazy for doing this. Yet, if she was going to get any clues out of this escapade, she’d have to move in for a closer look. Henny tiptoed across the front lawn to peer into the front windows. A soft, static-y voice repeated “book box” in her ears. How annoying and creepy, she thought. She couldn’t block it out as the chanting grew louder and clearer, “book box book box book box…” The way it channeled through her felt as if her brain was picking up a radio frequency.

Then, there she was, peeking around the corner of the house like a child–—a silver-haired lady in a prim blouse and skirt. Henny was certain she’d come face-to-face with the author depicted on the back of Chantilly. The sight of her startled Henny and she felt ashamed to be caught peeping. But the woman didn’t look angry; in fact, she just stared right back at Henny. A slow, welcoming grin stretched the corner of the lady’s mouth. Henny’s heart was pounding faster now but she took one step toward the woman. That’s when the voice repeating “book box” turned into ear-splitting feedback that felt like it would rip open her skull. Henny grabbed her own hair in two chunks and pressed hard on her head to try to stop the screaming chorus of “BOOK BOX BOOK BOX BOOK BOX.” Everything went black.

#

Henny was snuggled up on the frontroom couch with her book and a throw blanket on her lap. “Front room” is a Chicago term for the living room in the front of a bungalow floorplan, while the rest of the rooms line up behind it all the way to the back porch. She could hear her mom in the kitchen in the middle of the house talking on the phone to the doctor. “She had a panic attack in the middle of the night. A family friend found her passed out on the sidewalk in front of the little lending library.” Her mom repeatedly responded “uh-huh” to whatever the doctor was saying.

Dang, Henny thought. Just when she had come so close to meeting her author crush, she had been foiled by her stupid panic attacks. What timing. She couldn’t even remember how she got there. The last thing she recalled was staring up at Alderman Jordanski’s face from where she lay on the sidewalk. How embarrassing, of all people to find her. But she had barely noticed him in her daze, her attention drawn by the sky behind his head, a pre-dawn haze between night and day. How long had she been lying there?

Henny loved being able to see the moon when the sky was turning blue. The moon belonged to the night, but there it was, a day-moon glowing white against the blue-gray sky. It always made her wonder if only she could see it or if others saw it, too; a strange thought to have when waking up on a sidewalk, staring at the Alderman.

This was far from the first time a panic attack had spoiled something for Henny. The episodes had occurred ever since her father’s sudden death. Her mom had tried to get Henny help again and again, hoping they’d find anything that could work for her. Henny’s doctor would tweak her dosage, and she’d once again retreat into books to avoid all the triggers.

“Buried in a book again, Henny girl?” Her mother teased as she came back into the frontroom. “Is that the one written by the local author?”

“Chantilly, yep.” Henny held the book tight to her chest.

“Must be a good one,” her mom replied. “Doctor Dhali is going to call in your prescription, sweetie.”

Henny felt something was different about this attack. She didn’t feel like shying away; she wanted to go back and talk to that author. When her mom went to Walgreens to get her new meds, Henny snatched a few of Aunt Lil’s journals again and went to her bedroom to pore through them.

Aunt Lil’s journals had sections for contacts, appointments and notes. Henny went through pages and pages of random details related to the stories Aunt Lil had written for the Chicago Tribune. It ran the gamut of dirt on local politicians, new building projects and the human toll of gun violence. Henny skimmed them all for the words “thrash,” “wallop,” or anything related to Francis. Something snagged her attention—a mention of her father, Henry Marvell. Her dad was serving his third term as Alderman when he had his fatal heart attack. His name was mentioned in Aunt Lil’s notes regarding a story about plans for a condo building that included affordable housing units. In this neighborhood, affordable housing was a controversial topic. Supporters thought affordable housing should be spread equitably throughout all the city’s neighborhoods, to help keep a roof over the head of the vulnerable, such as veterans, the disabled and other people who could use a break. The detractors thought it would bring in the riff raff from the ghettos and wanted to maintain a perceived “whiteness” of the neighborhood. They wouldn’t say it exactly like that, but that’s what it amounted to. Truth is, most applicants for affordable housing came from their own neighborhood. Her dad was a staunch supporter of racial justice. He ruffled the feathers of people around him who didn’t want to acknowledge the darker parts of themselves. Their mindset was “I’m all for helping people, but not in my neighborhood.”

Although Henny was much younger back then than she is now, she had a sense of how ugly politics could get when she’d hear her parents talking about having their car towed for no reason, or a pile of dead fish left in the alley behind her dad’s campaign headquarters. Dead fish reminded her of smarmy Alderman Jordanski, and they were most likely his calling card. Everyone knew how politics worked in Chicago. Henny wondered if Jordanski ever felt guilty about how hard he had campaigned against her dad.

Henny noticed a note scrawled out in the margin and circled in red: “Lace = tell-all novel.” Lace? Could that mean Chantilly? It had to be. Chantilly was about a local political family. She had so many questions for Francis Thrash now.

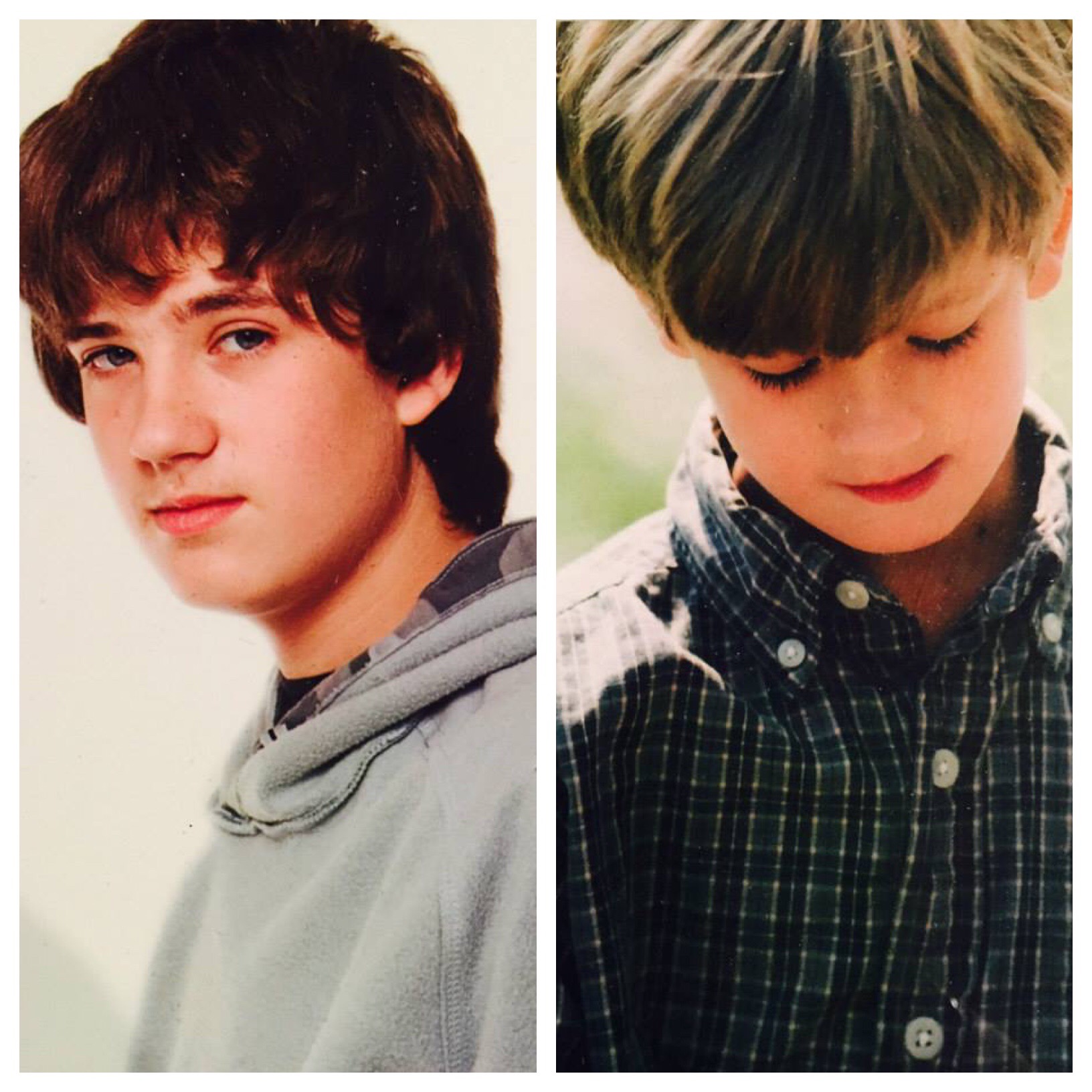

On one of the last few pages of the journal, Henny spotted a date, also circled in red: March 6, 2015, the date her father died. Next to it were her father’s initials, HM, for Henry Marvell. After that, the notes became sparse. Some pages only contained doodles. Henny knew it was during the fall of 2015 that they began to notice Aunt Lil’s decline. It started with little things, like Aunt Lil going places and forgetting how to get back. A year later it got worse. The doctors said it was caused by mini-strokes. Being a smoker didn’t help, and neither did her high-stress profession. A year later, Aunt Lil came to live with Henny and her mom.

Henny tore herself from her investigation to check on Aunt Lil. She found her snoozing in her chair and tucked the blanket in around her.

“That you, Henry?” She stirred and asked about her dead nephew.

“No, it’s me Henny.”

“Don’t let your mom know that your dad’s been talking to me, Henrietta.”

“You got it, Aunt Lil.” That’ll be an easy promise to keep, Henny thought darkly. She pondered how they were all connected: Aunt Lil the journalist, Francis Thrash the author and her dad the former Alderman.

“Bible river slope runner and the goose got wonder and wallop!” Aunt Lil said emphatically. Henny and her mom were used to these nonsensical outbursts. They usually just changed the subject. But when Henny heard the word “wallop” she wrote the whole phrase down so she could remember it. Could “wonder” stand for her own last name Marvell?

It was early Sunday morning when Henny slipped out to visit the author’s house again. This time she’d keep it together; the new medicine would help. She strolled by the book box and over to the house of Francis Thrash. She braced herself as she stood in front, telling herself to breathe. She heard the weird radio waves tuning in, “book box book box book box,” but this time it was a hum and didn’t overwhelm her. She saw Francis in the same spot, peeking around the corner. Henny walked toward her slowly.

“C’mon girl,” the author said kindly, “We have so much to talk about.”

Henny followed her down the slender gangway between the houses and into her backyard. The author took a seat on the patio and motioned for Henny to sit in the other chair.

“Thank you, Ms. Thrash.”

“Please call me Francis. We’re both writers after all.”

“Okay, Francis. How do you know I’m a writer?”

“It takes one to know one.”

Henny liked Francis immediately.

“Actually, I knew your Aunt Lil the reporter and your father the Alderman. Your mom, too.” Francis continued.

“Really?”

“Oh, yes. Your dad was really something. So articulate and so fierce in his convictions. He could really get a crowd worked up.”

“I remember that not everyone liked him. But I was just 11 when he died. Do you mind if I take notes?” Henny pulled out a spiral notebook.

“That’s fine with me. Your dad’s enemies were ruthless.”

“My dad would always tell me their bark was worse than their bite.”

“Until it wasn’t.” Francis rubbed her two hands together.

“Are you cold?” Henny asked.

“Always.” Frances waved off the concern. “Let me tell you a story about your dad and your Aunt Lil.”

Henny was enthralled; it was like being halfway through a good book —the part that makes you hope it never ends. She felt a powerful connection with this woman, as if Francis was her best friend and mentor wrapped together. They chatted and joked like they’d known each other forever. It was as easy talking to Francis as it was talking to herself.

“There was a time when your dad pushed the buttons of the wrong guy,” Francis went on. “I was working with him and your Aunt Lil; they were consulting on my novel. I overheard their phone calls and whispered discussions. You can’t believe what people appeared willing to do for the pettiest of grievances.”

“Some people are such a pain,” Henny agreed.

“You have no idea,” Francis emphasized.

There was a rustling of birds nearby; Francis looked at the sky.

“I need to go now. Same time, same place tomorrow? Let’s keep this our little secret,” Francis smile conspiratorially, eyes gleaming.

Henny nodded. Nothing would stop her from returning with her notebook for a chat before school. If her mom asked, she’d tell her that she was training for track & field tryouts in order to respect Francis’ request to keep their conversations confidential. Plus, she liked the idea of a secret rendezvous.

“I’ll be here,” Henny nodded, suddenly feeling as light as a balloon at a birthday party.

The next day, Henny showed up as promised … and the next day, and the next day after that. Henny learned how her dad, Aunt Lil, and Francis had been the Three Amigos. They were full of big ideas to make the world a better place, starting with their neighborhood. But her dad’s constituents rarely agreed on how to go about improving their neighborhood. Heated discussions turned into bitter battles on social media. Fundraising events turned into protest rallies. Francis’s stories were colorful and filled in many of the more grown-up details that Henny was too young to understand at the time. One of her dad’s biggest opponents, Jaquelyn Garfield, had been having an affair with the chief of police. She was Jordanski’s campaign manager during his first run as Alderman, and they were still bitter over their loss. As Francis weaved through the details, the story began to sound familiar. Something in Henny clicked.

“You mean the family in Chantilly is my family?” Henny asked.

“Yes and no. It’s fiction based loosely on fact. Journalism was your Aunt Lil’s territory. She fought for the truth. Fiction is my bag. I reveal the truth in my own way. It was getting to a point where no one knew what or who to believe, so why not spin it all into a story without any pretense of reality? I changed the names to protect the guilty.”

Henny wanted to get back home and finish reading Chantilly as soon as possible. It made sense now why she was so absorbed in the story. It had triggered memories she thought she had long forgotten. She looked at Francis Thrash and thought admiringly, I could talk with this woman forever.

“Henny, that’s all for today. Tomorrow I will share with you the biggest story of all, the story of Operation Rat. And then it will be time for the last chapter,” Francis said with misty eyes.

Henny’s heart dropped. She didn’t want their chats to end. Francis picked up on her emotions and assured her that she would understand once all was revealed tomorrow.

Henny returned home and went about the rest of her day in a daze. She chatted with her mom and aunt on auto-pilot. She muddled through until her at-home school day was over and she could return to her book.

“Your nose is going to get stuck in that book,” her mom teased.

“Oh Fancy Nancy, our Henny Penny is just a wordy nerdy. Who cares,” her Aunt Lil chimed in. They all giggled and Henny went back to reading.

The next day, Henny popped awake before dawn. She was both anxious and excited to hear what Francis was going to tell her next. She was ready for the day in a matter of moments and set out just as the sky was brightening.

Henny’s mom, Nancy, lay awake as she heard the door open again. She knew Henny lied about practicing for track & field. Her daughter never came back sweaty and was always carrying a notebook around. After the incident in which Alderman Jordanski found Henny on the sidewalk, her mom had been consulting regularly with Dr. Dhali. The doctor assured her that some fresh air and exercise were good for Henny and advised Nancy to let her daughter have her space. But after Nancy got a call from a neighbor about Henny sitting on their back patio in the early morning every day, her alarm bells went off. Today, she would follow her daughter and find out what was going on.

#

Henny felt tingly anticipation when she reached their meeting spot—that, and maybe a little dread. What did Francis mean by “all will be revealed?” Henny sat in her chair and tilted her head to the sky, soaking up the crispness of the fall morning. Then slowly, that insistent voice raced in her mind, “book box book box book box.” She squeezed her eyes shut, and when she opened them, Francis was sitting next to her. The voice in her head stopped. Something was different in Francis’s eyes today; they looked cloudy, like the sky before a storm.

“I saw it, Henny. I saw him do it. It didn’t register until much later. I saw him put white powder into one of the cocktails at the bar. He saw me watching and said it was medicine for his ulcer. But then he must have somehow switched the glasses so that your father got the one with the strychnine.”

“Strychnine. Isn’t that poison?”

“Rat poison. If the right amount is ingested, it can stop your heart. Over time, it can cause organ failure or brain damage.” She began speaking more stridently, her voice high-pitched and desperate, pleading for Henny to understand.

“Who did this?” Henny urged.

“Ed Jordanski and Jaquelyn Garfield his hateful campaign manager—both still livid after they lost the race against your father.” She spat the words out.

Henny felt a wave of shock. She watched her hero crumble and tried to process what she had just heard. Jordanski killed her dad over stupid local politics? Over who gets to fill the potholes in the street and cut the ribbons when a new business opened up? The gibberish her aunt was spewing the other day suddenly came back to her. Jordanski and Garfield. “Bible river slope runner and the goose got wonder and wallop.” It dawned on Henny that “bible river referred to “Jordan,” as in the River Jordan and “slope runner” referred to skiing, hence Jordanski. “Goose” was a reference to Garfield Goose, a popular old children’s TV show. “Wonder” must be a synonym for Marvell, for her dad. Translation: Jordanski and Garfield got Marvell and Thrash. But Francis Thrash was sitting right here, in front of her. Had Jordanski tried to harm Henny’s new friend?

While Henny processed all this, Francis Thrash had been quiet, letting everything she said sink in. But now she continued urgently, “Henny, that’s not all I have to tell you. We need you to finish the story. You see Henny, he got me too. Not right away, but he did. He knew I could be a threat. I hadn’t really put it all together until after the fact. Good people don’t always think of the evil things that others are capable of. Yet by then, it was too late; he’d already gotten me.” Her words choked out between sobs.

“Oh no, Francis, are you okay? Are you sick?” Henny reached out for her hands. Francis pulled away. “You will know what to do,” Francis said as she stood and walked away. “Goodbye, Henny.”

Henny felt panic set in as she watched Francis leave. She felt the familiar thumping in her head and knew that she had to get out of there.

#

There’s a feeling that every parent knows, that icy fear that something is terribly wrong with your child. Nancy felt that now. She would help her daughter no matter what it took, like she had through her every panic episode, the same way many parents do when their children struggle with mental illness. Her senses were dialed up to full lioness mode. She concealed herself in the bushes and peeked through a tiny crack between the fence slats into the neighbor’s backyard. She didn’t want to aggravate the situation with a confrontation, but she was ready to pounce. Henny’s trespassing had to stop, and Nancy needed to know why her daughter was doing this. At first, it hadn’t dawned on Nancy that this was Francis Thrash’s house, the author of the book Henny was reading. Her husband and Lil would meet there years ago to talk politics, but Nancy had always stayed out of it.

Henny was talking to someone, but Nancy couldn’t see who it was. She detected her daughter’s agitation nearing toward panic. She moved toward the gate, but before she reached it, her daughter bolted past her in a blind rush. Nancy took a quick peek into the backyard, but the other person had already gone. She took off after her daughter, calling her name.

Henny beat her mother home and burst into their frontroom where Aunt Lil was sitting in her chair, talking to her dead husband as usual. Henny was pacing the room and babbling when her mom caught up.

“Henny,” she coaxed, “Will you sit please? We need to talk.”

As mother and daughter sank into the couch, Henny started trying to explain, but her words tumbled out; “I talked to the author of Chantilly, Mom, to Francis Thrash. She told me everything. I know how dad died, how he really died. Francis Thrash saw it, and now I think she’s sick.”

Her mom tried to hide her horror. “Henny, that’s not possible,” she gasped.

“Sick?” Aunt Lil piped in, “Francis Thrash has been dead for years.”

The words rang in Henny’s ears. She grabbed her phone and googled Francis Thrash. Her obituary was the first thing to pop up. No. No. No. She should have kept searching the internet instead of playing Nancy Drew. She threw her phone across the room.

“I thought you knew, Henny,” her mom said but her voice sounded far away.

How was this even possible? Henny thought, stricken with panic. She fought the sensation of the room melting around her. She ran to her room and locked the door. She craved the sanctuary of her book. There, on her comforter, was Chantilly. She grabbed it. She needed to see how the story ended now. As she flipped through the pages, the words slid off. She dropped the book back on the bed. Her head was throbbing the words “book box” in time with her mother pounding on her bedroom door. Her mom stopped knocking, and Henny heard muffled voices further away. “Hello Ed, I didn’t hear you come in.” Jordanski, her father’s murderer, was back in the house —their house. Henny looked out her window at the tree within reach, an easy climb down.

#

“Can I get you a cup of coffee, Ed?” Nancy offered as he sat at her kitchen table.

“Please and thank you. Is Henny okay?”

“I think that book she’s reading spooked her into an episode. She didn’t know that Francis died several months after her dad. She was too young, I guess.”

“Not too young anymore. I’d like to get a look at that book, out of curiosity. I didn’t think Francis ever finished it.”

“I know, right? Let me see if I can slip it out of her room. She probably wore herself into a nap after that last episode. I just need to grab the key. Hang on a sec.”

Ed Jordanski looked around the tidy kitchen and thought about the circumstances that had passed over the last several years. What was in that book? Would there be a bombshell revelation? He touched a small vial of white powder in his pocket.

His thoughts strayed to Nancy. Nancy Marvell was a sweet lady and serious wife material now that she was a widow. His last relationship had ended badly, and the restraining order his ex filed against him was a stain on his reputation. Luckily, his followers didn’t care. Could he help being a man in love? He’s a passionate guy, Jordanski rationalized. But running the Ward was his passion above all else. Relationships were trouble. His true calling was defending the neighborhood, and he wouldn’t tolerate anyone sabotaging his ambitions. His thoughts halted the minute Nancy walked back into the kitchen. Her face looked stricken, and her eyes were wide. She gestured for him to look at the book Henny had found in the book box. Together they flipped through Chantilly —a book of entirely blank pages.

“She’s been reading a blank book for days?” Nancy queried, horrified. “And now she’s snuck out her window.” Nancy quickly grabbed her phone and car keys. She needed to find her daughter, but she’d need to hurry back for Aunt Lil. As a parting thought, she turned back to Jordanski. “You coming, Ed?” He shook his head and Nancy left without him.

#

Jordanski sat at the bar of The Council, a popular watering hole for city politicians, reporters, and political groupies. The bartender placed two draft beers from a local brewery in front of Jordanski with a nod, and then slid to the other end of the bar. This establishment had been around for decades, and the bartender nearly as long. He knew when people wanted to chat and when they wanted to be left alone, same as always. The interior hadn’t changed much either; dark wood, dim lighting, and no frills. Photographs of famous Chicagoans lined the perimeter—Mayors Harold Washington, Jane Byrne, and both Daley’s. Chicago’s history had seeped into the walls. Legendary reporter Mike Royko was next to a smaller photo of a young Lil Holiday, known affectionately to Henny as Aunt Lil.

Jaqueline Garfield returned from the ladies’ room and sidled up next to Jordanski. She caught him gazing at Lil’s photo.

“So what’s the verdict on old Lil these days?” Garfield whispered, leaning in, her face mask dangling from one ear.

“In all the time I’ve been hanging around their house, she’s said some crazy shit. But she’s never brought up anything about the goings-on in this bar or the untimely deaths of the good Alderman Henry Marvell and the author Francis Thrash.”

“Thank God. I’d hate it if we had to bump off an old lady.” She gave him a sly half-grin.

“Bump off? You sound like you’re in an old gangster movie.”

They smiled conspiratorially. They enjoyed being thugs. Jordanski took a long sip of his beer and thought about what he wanted to say next.

“Jackie, we did what had to be done, no doubt about it. Sometimes I have to remind myself that it was for the greater good. We couldn’t let the bleeding hearts ruin our little slice of Mayberry by bringing in the riff raff with affordable housing.” Jordanski paused, shaking his head. “The idea of us being racist—you know I have a Black drinking buddy.”

“Ludicrous.”

“The rapper? No, I mean Harold,” Jordanski corrected her.

“I mean it’s ludicrous to think that we’re racist for wanting to protect the neighborhood.”

“Right, I knew that. I’m messing with you.”

“And I’ll always have something on you, my friend,” Garfield teased.

“Uh-huh,” Jordanski responded mildly.

“What about that kid, the girl with the book?” Garfield asked.

“She’s a nosey little bitch, but she’s crazier than her Aunt Lil. Non-issue.”

“How so? Wasn’t she reading that Thrashy-Trash tell-all novel?”

“That’s the thing. She was pretending to read a book, but there is no book. Thrash never finished it. All of her files and computer were destroyed after she died; our team made sure of it. So even if she started a book, it’s long gone. The girl was flipping through a book with blank pages, for Christ’s sake.”

“So with Aunt Lil’s health declining and this disturbed girl headed for the loony bin, do you think we’re finally in the clear?” Garfield moved a few inches closer. Jordanski could smell the beer on her breath. She hadn’t seen him slip the white powder in her drink when she visited the ladies’ room.

“That’s why I invited you here today; to toast to it being over. Here’s to no more loose ends.” Jordanski raised his glass.

#

A year had passed before Henny visited the book box again. In all that time, Henny was unable to convince her mom that Jordanski murdered her father and Francis Thrash. Her mom just kept reaching out to Dr. Dhali, who in turn, kept upping her meds. Not that she could blame them. Something about talking to dead authors and obsessive reading of a blank book that freaks people out.

Jordanski never came over to their house anymore. It was another election year and he was looking for a new campaign manager. Plus, he thought Henny was nuts. Just as well. After sneaking out of her bedroom window that day, she returned the same evening when she was sure Jordanski was gone. She just couldn’t worry her mom that way.

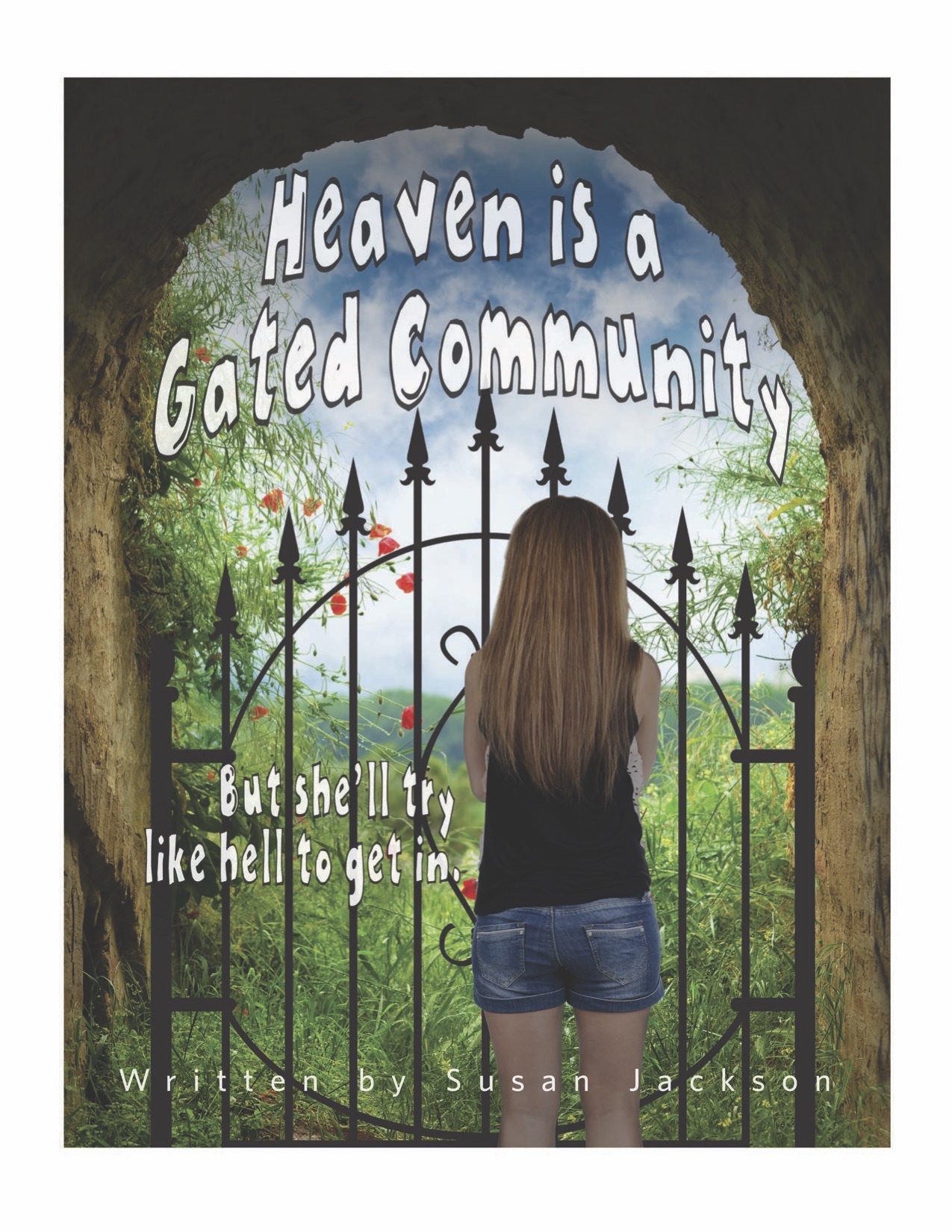

Today, exactly 12 months later, Henny opened the little door to the book box once again. This time, she placed a pristine paperback inside. Her mom had helped her learn about self-publishing and was delighted about her daughter’s new writing hobby. Henny thought about the story she had written coming out to the public. It could be dangerous, but she didn’t care. She felt changed and fearless. Henny would never again doubt Aunt Lil’s conversations with her dead husband. She would forever be humbled by the power of the book box. The book box gifted her with Chantilly. She was truly the person who it was meant for, the only person. This book was a conversation between the living and dead. Or maybe it was all a product of her imagination, a strange ability indeed. It’s long been theorized that people with mental illness hear things that sane people are incapable of hearing. The proverbial voices in their head may in fact be messages from those who’ve passed. Those voices helped Henny finish writing this novel. She saw them standing there in the yard—her dad wearing the blue tie he wore for press conferences, Francis Thrash and now her Aunt Lil, who had left them a few months ago. Her dad gave her a nod. Henny had a stack of books in her backpack, and she would drop one off at every book box she could find in Chicago. Book box, book box, book box indeed. She picked up the book one last time to inhale that new book smell. She gave herself a moment to admire the cover: Chantilly: An Unreal True Story, by Henny Marvell and Francis Thrash. Could there be anything else as satisfying as a good book? Henny didn’t think so.

<<<<<>>>>>